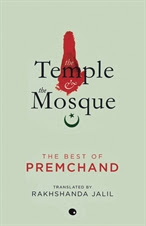

When Dhanpat Rai( better known by his pen-name Munshi Premchand) breathed his last in 1936, he left behind more than a dozen novels and about three hundred short stories, all of which are now firmly in the canon of Hindi-Urdu literature. There’s perhaps no Hindi curriculum in India which does not have a bit of Premchand in it. When you look at an output like that, you would normally expect a “best-of” anthology to be more than 197 pages, which is what “The Temple & The Mosque: The Best of Premchand” comes up to.

That is perhaps the only complaint one can have against this excellent collection of 17 vintage Premchand stories, translated by Rakhshanda Jalil, who has, in the past, translated works by Manto and Phanishwar Nath “Renu” among others. Readers familiar with Premchand’s oeuvre will find many of his most celebrated stories here, like “A Winter’s Night” (Poos Ki Raat), “The Shroud” (Kafan), “Idgah”, “A Tale of Two Oxen” (Do Bailon Ki Katha) and “Salvation” (Sadgati). For a newcomer, this book is as good a place to start as any.

Premchand’s status as social chronicler extraordinaire is in focus in the titular story “The Temple & The Mosque” as well as “Salvation”. In the former, Chaudhry Itrat Ali, a devout man who observes the Sharia strictly and takes a dip in the Ganga every morning; feels compelled to take matters into his own hands when he sees his tolerance and inclusiveness in vain amongst a town of fanatics. When he goes out of his way to protect Thakur Bhajan Singh, his “Rajput Man Friday”, his actions have familiar, escalating consequences.

“The Muslims said to themselves that Chaudhry sahib had by now lost all the vestiges of the faith he had been born into. The Hindus saw it as the ripe moment for performing Chaudhry saheb’s shuddhi- the purification rite that would cleanse him of any remaining impurities. The mullahs increased the volume of their preachings and the Hindus, too, raised the flag of Hindu solidarity.”

This sort of scathing, bleakly funny commentary on the vagaries of social existence in early 20th century India( particularly in rural settings) is, of course, what we’ve all come to associate Premchand with. While the titular story and “Intoxicants, Both!” bring out religious conflicts of very different kinds, “The Thakur’s Well” and “Salvation” prominently feature the plight of the untouchables. “Salvation” (Sadgati) which is one of Premchand’s most frequently anthologized stories, features as protagonist Dukhi, a tanner or chamar, an “untouchable” caste, who is forced to chop an obstinate tree on the premises of Pandit Ghasiram, the village priest. Reason: so that the priest can pick out an auspicious date for the wedding of the poor tanner’s daughter. The innate hypocrisies and lack of empathy in the caste system are laid bare in this gem of a tale. In an unforgettable scene, when a tired Dukhi asks for fire to light a pipe, the Pandit’s wife, anxious not to touch him, inadvertently drops a spark on his head.

“With her face covered by a veil, she threw the coals at Dukhi from a distance. One large spark fell on his head. He drew back in alarm and starting tearing at his hair in sudden pain. He thought to himself, this is the result of polluting a Brahmin’s sacred home. God is so quick to mete out punishment. No wonder then that the entire world so rightly fears pandits. You hear all the time of people being robbed and cheated; let someone try and rob a pandit of his money, then he would know! The thief’s entire clan would be destroyed and his limbs would rot and fall away.”

The injustices of the caste system, the vicious circle of poverty, social ostracism, usury and the evil moneylender; these motifs became synonymous with Premchand’s works, especially with younger readers. These generations were not as attuned as their parents were, to the still-wide chasm between the haves and the have-nots in India. Moreover, they were also assaulted by an avalanche of Premchand stories (and always this particular kind of story) in textbooks, and on the TV or the silver screen. Uninspiring translations of his stories also did not help matters. (The late, rather underrated author Shama Futehally wrote a charming little piece about this, collected in “The Right Words” a posthumous anthology published by Penguin in 2006) As a result, two things happened. One, Premchand was perceived as a bit of a one-trick pony, even among people who were well-versed in literary matters as a rule. Two, Premchand’s stories were sometimes criticized for being hackneyed and repetitive, which is ironical for someone who’s a pioneer of the modern Hindi short story, and has spawned scores of imitators.

This phenomenon is a bit like pegging Satyajit Ray down as a glorified balladeer for “the naked and the hungry”, based purely on the Apu trilogy. Skeptics taking this line of argument would typically ignore works which do not fall within this perceived category of sorts; the wicked urban jungle of Jana Aranya and Seemabaddha, the irreverently comic, fable-like Parash Patthar or the decadence of bleeding, fading aristocracy in Shatranj Ke Khiladi, which was based on a Premchand story (longtime Premchand readers will be a touch disappointed to discover its absence in this collection).

This is something translator Rakhshanda Jalil understands well; in an illuminating essay at the end of the book, she acknowledges as much, “The world of Premchand, at first glance, is a seemingly black and white one peopled by villains and martyrs, a bleak world of unending poverty, unbreakable caste barriers and an unyielding social order.” The real genius of this book lies in the fact that it sheds light on the many different kinds of authorial voices Premchand could and did take on. “Intoxication” (Nasha) tells, in a sharp-as-nails first person narrative, the story of a young man of modest means who discovers the ego-massaging effects of perceived affluence. “The Secret of Civilisation” (Sabhyata Ka Rahasya) burns with all the humanistic fervour and the indignation of Maxim Gorky, another stalwart who believed in bringing literature back to the Everyman, so to speak.

In Todd Haynes’ 2007 Bob Dylan biopic (I use “biopic” in a very loose sense of the word) “I’m Not There”, Christian Bale’s character Jack Rollins (alter-ego for the 60s Dylan) observes bitterly, “All they want from me is finger-pointing songs…I only got ten fingers.” Like Dylan, Premchand, too, has taken a lot of flak because of preconceived identities thrust upon his work. As Dhanpat Rai, he lived in a time and a place where the unspeakable was very often the unspoken, too. As Premchand, he merely voiced, from time to time, what he felt had been silenced for far too long. This collection showcases the full range of his powers and confirms his place as quite simply, one of the greatest Indian writers of all time.